The Origins Of Jewellery

Jewellery comes in multiple designs and materials and has been on a constant move throughout the ages. As we may have mentioned earlier, jewellery is not just about body adornment. It reflects who we are people, our beliefs, our ways of living and loving.

Here is an article from Victoria and Albert Museum, the world's leading museum of art and design.

A History of Jewellery

Ancient world jjewellery

Collar known as The Shannongrove Gorget, maker unknown, Ireland, late Bronze Age (probably 800-700 BC). Museum no. M.35-1948. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Jewellery is a universal form of adornment. Jewellery made from shells, stone and bones survives from prehistoric times. It is likely that from an early date it was worn as a protection from the dangers of life or as a mark of status or rank.

In the ancient world the discovery of how to work metals was an important stage in the development of the art of jewellery. Over time, metalworking techniques became more sophisticated and decoration more intricate.

Gold, a rare and highly valued material, was buried with the dead so as to accompany its owner into the afterlife. Much archaeological jewellery comes from tombs and hoards. Sometimes, as with the gold collars from Celtic Ireland which have been found folded in half, it appears people may have followed a ritual for the disposal of jewellery.

Medieval jewellery 1200–1500

Pendant reliquary cross, unknown maker, about 1450-1475. Museum no. 4561-1858. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The jewellery worn in medieval Europe reflected an intensely hierarchical and status-conscious society. Royalty and the nobility wore gold, silver and precious gems. Humbler ranks wore base metals, such as copper or pewter. Colour (provided by precious gems and enamel) and protective power were highly valued.

Until the late 14th century, gems were usually polished rather than cut. Size and lustrous colour determined their value. Enamels - ground glasses fired at high temperature onto a metal surface - allowed goldsmiths to colour their designs on jewellery. They used a range of techniques to create effects never since surpassed.

Some jewels have cryptic or magical inscriptions, believed to protect the wearer.

Renaissance jewellery

Ring, maker unknown, setting 15th century, centre 2nd century BC-1st century BC. Museum no. 724-1871. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

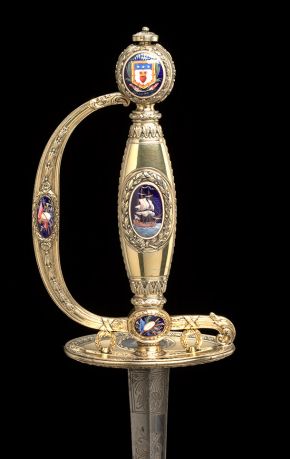

Renaissance jewels shared the age's passion for splendour. Enamels, often covering both sides of the jewel, became more elaborate and colourful. Advances in cutting techniques increased the glitter of stones.

The enormous importance of religion in everyday life could be seen in jewellery, as could earthly power - many spectacular pieces were worn as a display of political strength.

The designs reflect the new-found interest in the classical world, with mythological figures and scenes becoming popular. The ancient art of gem engraving was revived. The inclusion of portraits reflected another cultural trend - an increased artistic awareness of the individual.

17th-century jewellery

Necklace with Sapphire Pendant, bow about 1660, chain and pendant probably 18-1900. Museum no. M.95-1909. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

By the mid-17th century, changes in fashion had introduced new styles of jewellery. While dark fabrics required elaborate gold jewellery, the new softer pastel shades became graceful backdrops for gemstones and pearls. Expanding global trade made gemstones ever more available. Advances in cutting techniques increased the sparkle of gemstones in candlelight.

The most impressive jewels were often large bodice or breast ornaments, which had to be pinned or stitched to stiff dress fabrics. The swirling foliate decoration of the jewels shows new enthusiasm for bow motifs and botanical ornaments.

18th-century jewellery

The end of the previous century had seen the development of the brilliant-cut with its multiple facets. Diamonds sparkled as never before and came to dominate jewellery design. Frequently mounted in silver to enhance the stone's white colour, magnificent sets of diamond jewels were essential for court life. The largest were worn on the bodice, while smaller ornaments could be scattered over an outfit.

Owing to its high intrinsic value, little diamond jewellery from this period survives. Owners often sold it or re-set the gems into more fashionable designs.

19th-century jewellery

Spray ornament, maker unknown, about 1850. Museum no. M.115-1951. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The 19th century was a period of huge industrial and social change, but in jewellery design the focus was often on the past. In the first decades classical styles were popular, evoking the glories of ancient Greece and Rome. This interest in antiquities was stimulated by fresh archaeological discoveries. Goldsmiths attempted to revive ancient techniques and made jewellery that imitated, or was in the style of, archaeological jewellery.

There was also an interest in jewels inspired by the Medieval and Renaissance periods. It is a testament to the period's eclectic nature that jewellers such as the Castellani and Giuliano worked in archaeological and historical styles at the same time.

Naturalistic jewellery, decorated with clearly recognisable flowers and fruit, was also popular for much of this period. These motifs first became fashionable in the early years of the century, with the widespread interest in botany and the influence of Romantic poets such as Wordsworth. By the 1850s the delicate early designs had given way to more extravagant and complex compositions of flowers and foliage. At the same time, flowers were used to express love and friendship. The colours in nature were matched by coloured gemstones, and a 'language of flowers' spelt out special messages. In contrast with earlier periods, the more elaborate jewellery was worn almost exclusively by women.

Arts & crafts jewellery

Pendant-brooch (detail), designed by C.R. Ashbee and made by the Guild of Handicraft, about 1900. Museum no. M.31-2005. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Developing in the last years of the 19th century, the Arts and Crafts movement was based on a profound unease with the industrialised world. Its jewellers rejected the machine-led factory system - by now the source of most affordable pieces - and instead focused on hand-crafting individual jewels. This process, they believed, would improve the soul of the workman as well as the end design.

Arts and Crafts jewellers avoided large, faceted stones, relying instead on the natural beauty of cabochon (shaped and polished) gems. They replaced the repetition and regularity of mainstream settings with curving or figurative designs, often with a symbolic meaning.

Art Nouveau jewellery and the Garland style 1895–1910

Hair ornament, made by Philippe Wolfers, 1905-7. Museum no. M.11-1962. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The Art Nouveau style caused a dramatic shift in jewellery design, reaching a peak around 1900 when it triumphed at the Paris International Exhibition.

Its followers created sinuous, organic pieces whose undercurrents of eroticism and death were a world away from the floral motifs of earlier generations. Art Nouveau jewellers like René Lalique also distanced themselves from conventional precious stones and put greater emphasis on the subtle effects of materials such as glass, horn and enamel.

Leave a comment